December 17, 2024

Baird Symposium Author Karen Russell and Cultivating the Idiosyncratic

As you enter our 42nd Baird Symposium author Karen Russell’s phantasmagoric world, you’ll encounter the uncanny – mutant scarecrows, wolf-like girls, and vampires – just as easily as you’ll be on familiar ground at the shopping mall. It’s all strangely familiar and a bit off, like the magic realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, one of Russell’s literary touchstones where, in this surreal landscape, we can see ourselves and the human condition most vividly.

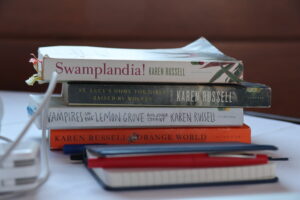

The author of three novels and three short story collections, her debut 2011 novel Swamplandia was a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. In 2009, the National Book Foundation named Russell a five under 35 honoree. She also received a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant” in 2013. Russell has taught creative writing at the University of California, Irvine, Williams College, Columbia University, and Bryn Mawr and was endowed chair of creative writing in the MFA program at Texas State University.

During her workshop with our senior symposium class, Russell trod the familiar territory of the ghost story the students were composing. In a certain respect, this genre of stories mirrors real life in that terrible circumstances occur to good individuals arbitrarily, Russell said. One student shared her story of a group of friends who were animals, and another student told of a concept of pinhole photography inspired by artist Robert Calafiore, who visited KO earlier in the semester. Russell explained the formula for a ghost story as a stable context that has been disrupted – an unsettling one that lurks beneath the surface of our everyday lives.

“You’re working in your ordinary day,” Russell said. “And then a mysterious force has shown up with this urgent demand, and it won’t leave you alone. It’s literally rattling the furniture. Even if you are not writing about a supernatural force in your story, something is always haunting a character in your story. Being alive and conscious and having a past is a deeply haunting experience.”

Following the workshop, Russell spoke at an assembly about her craft. She shared with the students how fortunate they are to be at an age where they are granted the freedom to be vital and awake before the banal realities of mortgages and tax returns set in. “You are free to see and know and feel things that adults become insulated from,” she said. She told the students how fortunate they are to have teachers who allow them to take risks and give them support to take those risks. “It’s more than helping students identify what is best and wildest and most idiosyncratic and most alive in them, what their passions are, and giving them wings and helping them to fly. It’s a gift to be at a place like this.”

As a child, Russell told the audience she was captivated by Ray Bradbury, Octavia Butler, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and more classic writers like Leo Tolstoy and F. Scott Fitzgerald. While at the public library, she questioned the ghettoization of books, segmenting them by type. She commented that even a novel as traditional as Jane Eyre begins with a haunting. Russell encouraged the students to read like an “omnivore” and not be closed off to embracing abstruse texts and poetry. She admitted that as a teenager, she chased her GPA and consumed work that required less brain power. One of her favorite teachers exposed her to an elliptical poem by Wallace Stevens, “The Order of Key West,” which granted her permission to be “bewildered.”

In her initial stabs at storytelling, she shared that she attempted to write what she perceived to be an adult, with adultery taking center stage, even though she was only 18. “I was trying to wear sensible pumps and write serious things,” she said. “I tried to portray the real world to whip married adults into plausible dramas to describe the makes and models of their cars.”

She described these stories as “flat cola,” lacking an “effervescent sense of creation” until her teacher encouraged her to write like the authors she loved: Marquez, Saunders, and Calvino. Despite their heavyweight literary merit, these authors used devices found in fables. “Here were writers of serious literature drawing upon the oneric power of fairy tale, borrowing the technique of uncanny estrangement from horror and science fiction, handing monsters the mic and letting them crack jokes.” Reading these stories allowed Russell to open her writing and explore other worlds, which, in their strangeness, allowed her to plumb the oddness of everyday experience.

A tension exists in fantasy writing where the writer must attend to realness, she said. “Writing something out there,” she said, “you have to be strictly attentive to the concrete detail than someone writing in a naturalistic vein because the greater the strain on credulity. The more convincing the properties in it have to be.”

The most challenging aspect of writing fantasy is convincing the reader to care about the characters, even if they might be she-wolves. “No matter how whacked out your story turns out to be, no reader can live in that world for long unless it also feels solid enough to support a genuine emotional connection.”

And there’s nothing more real than that.